Wintertime is one of the best times to watch large raptors, like hawks and eagles, in the Bitterroot valley. One reason is the big increase in numbers over the winter as raptors from Alaska and across northwestern Canada migrate south to spend the winter in Western Montana. Not only do local populations of hawks and eagles grow in the winter, but it also brings in a few species that are not generally seen in the area at all except in winter, like the Rough-legged Hawk.

Researchers from Bitterroot View Raptor Research Institute and MPG Ranch tracked the movements of Golden Eagles captured in the valley from 2011 to 2018 and determined, among other things, that these northern breeders return to the valley year after year.

efforts.

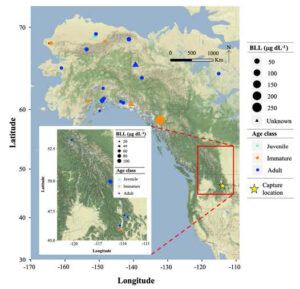

The eagles tracked included two juvenile, seven immature, and 20 adult, that were outfitted with GPS transmitters. Of these, 20 turned out to be migratory, and nine non-migratory. Most of the migratory Golden Eagles summered in Alaska, and the rest summered across the Yukon, British Columbia, and Northwest Territories, Canada. The average summer locations for migratory birds were over 900 miles from the capture location. In contrast, the average location for seven of the nine non-migratory Golden Eagles were within 90 miles of the capture location for the remainder of the year.

Blood samples were also taken from all of the captured birds before they were released to test for blood lead levels (BLL). Studies have shown that Golden Eagles are susceptible to ingesting residual lead fragments from hunted animals. If hunting occurs where Golden Eagles winter, both migratory and non-migratory Golden Eagles may be exposed to lead.

Kate Stone, Director of Avian Research at MPG Ranch, who also serves as a volunteer and as a board member of Wild Skies Raptor Center, tried unsuccessfully to save a Bald Eagle recently found in the Darby area that succumbed to lead poisoning. The bird, found by Kathy Richardson, showed initial signs of potential recovery but died within a week. The cause was identified in an x-ray that showed a small sliver of lead lodged in the bird’s gut. The lead most likely came from a carcass or gut pile of a large ungulate containing the shattered slivers of a lead bullet.

“We expected non-migratory Golden Eagles to have higher BLL than migratory birds because they might more frequently scavenge shot ground squirrels and prairie dogs, but BLL did not differ between non-migratory and migratory birds. Overall, our results show that lead exposure is widespread in Golden Eagles that winter in western Montana,” it states in the report.

This study, combined with one done on Bald Eagles in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, which found 98% of the birds had elevated BLL, with 25% of those having acute lead exposure (>100 µg/dL), builds evidence that BLL in Golden and Bald Eagles may be highest during and directly following the hunting season.

“We are working on publishing similar data from Bald Eagles captured here, and the trends are the same,” said Stone.

Direct mortality related to acute lead poisoning, however, is not the only issue.

Of the 91 Golden Eagles captured on their winter habitat in western Montana, nearly all of them (94.6%) had elevated BLL. Lead in blood is considered indicative of relatively recent exposure, meaning the eagles likely ingested lead in or around the Bitterroot Valley.

In addition to direct mortality, lead poisoning even at low levels can impair physiological processes and contribute to mortality, according to Stone. Some populations of Golden Eagles appear stable, whereas others do show potential declines. Various anthropogenic threats besides lead poisoning may contribute to these declines, such as habitat loss, reductions in prey base, vehicle collisions, electrocutions, and industrial wind energy. According to one study, lead exposure at sublethal levels may impair Golden Eagles enough to make them more susceptible to these types of fatality.

One recent study of Bald Eagles in the northeastern U.S. shows that mortality events of wild eagles that arose from the ingestion of lead interacted with expanding population dynamics in a manner that depressed the long-term growth rate of the population. The depression of the growth rate was estimated to be 4.2% in female eagles and 6.3% in male eagles.

“So, we’re not only concerned about the direct mortalities, which are horrible, but also of the associated impacts lead has on both individuals and populations,” said Stone.

It is noted in the report that, unlike the threats such as habitat loss and energy development, that require the cooperation of many stakeholders to find a solution, the solution to lead exposure is simple: hunters can use nonlead ammunition. To accelerate a transition to nonlead, state agencies, sportsman groups, and wildlife organizations are running outreach programs, such as hunter education classes, that encourage hunters to voluntarily switch. These efforts will be most effective in areas that have intense hunting and high densities of Golden Eagles, the report states.

“The big bonus here is that the lead problem is such an easy fix!” said Stone. “Conversations about lead ammunition are not at all about stopping hunting. They’re about asking people to consider that they have choices, and that the choices they make really matter.” Stone said she would encourage hunters to make the switch to non-lead ammunition for hunting at any time, but the shoulder season would be a particularly great time to consider lead alternatives, as eagle numbers are at their winter peak right now, other food resources are few and far between, and shoulder-season hunts can lead to concentrations of gut piles on the landscape that far exceed the dispersed nature of harvest during the general season.

“The aggregation of over 100 Bald Eagles southeast of Stevensville feasting on elk gut piles in the past week is good evidence of the numbers we can attract at this time of year,” said Stone. “We should be both amazed and also doing our best by these winter visitors. Indeed, in the absence of lead fragments, gut piles and other offal from hunting are a great resource for eagles and other scavengers.”

Anyone curious about how lead fragments, and how lead effects wildlife, or wondering how lead alternatives perform, can find information on the website www.huntingwithnonlead.org.

“Using copper for big-game hunting is quite mainstream now,” said Stone, “so it’s not hard to find people in the hunting community who have already made the switch. So, hunters likely have family and friends who could speak to their experience.”

Stone said it takes both finances and a physical and mental toll to treat animals suffering from lead poisoning. She said Wild Skies Raptor Center was currently treating another eagle suffering from lead poisoning in Whitefish.

“She is still in chelation treatment at Wild Skies and shows signs of improvement and lowering lead levels,” said Stone. “We hope she can be released to the wild, but with lead poisoning, birds that seem to be improving sometimes take quick turns for the worse.”

Financial donations can be made at www.wildskies.org