By Michael Howell

The late Doris Milner, longtime Bitterroot Valley resident and renowned wilderness advocate, was among the first dozen Montanans to be inducted into the newly established Montana Outdoor Hall of Fame at a ceremony in Helena on December 6, 2014. Other people inducted into the Hall of Fame that day include Granville Stuart, Theodore Roosevelt, Charles M. Russell, Senator Lee Metcalf, Thurman Trosper, Don Aldrich, Bud Moore, Cecil Garland, Ron Marcoux, Gerry Jennings, and Chris Marchion.

Jim Posewitz of Montana’s Outdoor Legacy Foundation, who led the effort to create the Montana Outdoor Hall of Fame, said of it, “Today’s treasured wild nature was restored from what was once the wildlife bone-yard of 19th century America. The Montana Outdoor Hall of Fame will capture, preserve, and teach the stories of the men and women whose conservation ethic helped protect Montana’s quiet beauty and grandeur for the benefit of future generations.”

Posowitz enlisted the backing of the Montana Historical Society and put together a collaborative effort including Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks; Montana’s Outdoor Legacy Foundation; the Montana Wildlife Federation; the Montana Wilderness Association; Montana Trout Unlimited and the Cinnabar Foundation to help create and sustain the Outdoor Hall of Fame in perpetuity. He said the induction of individuals into the Hall of Fame will also build public awareness and pass on to others Montana’s conservation heritage.

The first group of inductees was picked by the Board of Directors and includes citizens, government officials, hunters and anglers, farmers and ranchers; and people who have worked to protect everything from wilderness and water quality to fish habitat, big game, and endangered species. In the future people from across Montana and all walks of life will nominate candidates to be inducted.

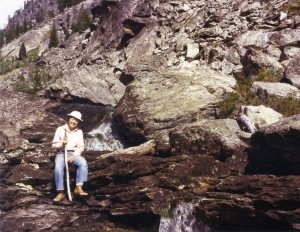

Doris Milner was born in 1920 and raised on a dairy farm in Maryland. She moved to the Bitterroot Valley in 1951 where she fell in love with the surrounding outdoors and became an ardent and active advocate for wilderness until her death in 2007. A plaque in her honor will hang in the Montana Historical Society building in Helena with the other inductees.

Milner’s plaque states in part: “First inspired by the threat of a timbersale along the Selway River in the Magruder Corridor, she went on to join Idaho Sen. Frank Church and Montana Sen. Lee Metcalf in expanding the wilderness to include the corridor and designating the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness.”

That was quite a fight. After their success, Senator Lee Metcalf put it this way in a letter to Milner, who was elected the first woman president of the Montana Wilderness Association in 1973:

“We have fought the good fight together… generations to come will acclaim the combined efforts of thousands of Montanans whether they be of Montana Wilderness Association, the Congress or others who fought to preserve the beautiful natural heritage which is ours… But the fight goes on. You may be sure I will continue to do all I can to hold the gains we have made and to build on them. I know I can count on the continued support of those Montanans who love the unspoiled beauty of our state to join this important effort.”

Milner is often quoted about how “mad” she got at the sight of a bulldozer one day on the Magruder Corridor.

At a dedication ceremony of a memorial sign placed at Nez Perce Pass at the entrance to the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness, John Gatchell, the Conservation Director of the Wilderness Association, recalled how Milner was interviewed on the 40th anniversary of the Wilderness Act by Elizabeth Arnold of National Public Radio, who traveled to Hamilton to interview Doris on her porch.

Doris told the story of how she got involved in the fight to save the Selway, saying, “All I knew is I was mad… and I was gonna do something about it.”

Seventeen years later, Doris stood with the President as he signed the bill expanding the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness and establishing the River of No Return.

Her son Eric Milner said his mother really got tagged with that comment. He admits that there was some anger driving her.

“She was mad,” he said, “but she was so much more. She was a formidable intellect. That’s why so many people were keen on getting her take on any major conservation issue in the state or the nation from 1963 to about 2005.”

Eric said his mother had an intellectual integrity that earned respect from every quarter. He said she was known for her willingness to listen to all sides on the most heated issues. If she didn’t have enough information on the issue she would withhold judgment until she herself was convinced enough to take a stand. Then she would set about convincing others, whether they were simply her neighbors, the Supervisor of the National Forest or members of Congress.

Orville Daniels, Forest Supervisor at the time, noted that his agency was often in conflict with Milner and the MWA at the time, but, “In spite of those conflicting opinions, there was genuine friendship between Doris and many of us in the Forest Service. Agency scientists, regional and national leaders and local folks all made the trek to her home or kept in phone contact in order to share information and ideas. Ultimately this relationship led to Doris being named to the Secretary of Agriculture’s national Multiple Use Advisory Board and so her influence was taken to a higher national level. It is not always normal to have such respect between activists/advocates and the Forest Service organization.

“Her environmental credentials were always impeccable,” he said. “However, unlike others – Doris was not motivated by her ego. She was motivated by what was the right thing to do. She had strong beliefs, worked hard to know and understand the facts, was great at networking (although she would not have used that term) and she was passionate in her beliefs.”

As Gatchell put it, “She did it all with passion and eloquence, personal integrity, and a wonderful sense of humor.”

Eric said that knowing his mother as he does he would not characterize her as being driven by anger to do what she did for the wilderness for so many years.

“It was more like she had a calling,” he said. She had a positive vision of what was worth preserving and she went after it, he said.

He said he was gone from the area for many of his mother’s most active years “but when I returned it was clear to me how concerned she was and over so many issues.” He said they have donated her papers to the Mansfield Library at the University of Montana.

“As far as being placed in the Montana Outdoor Hall of Fame? I’m sure she would be pleased. She was an outstanding candidate for that, out of a number of candidates. It’s an honor she deserved,” said Eric.

Another Outdoor Hall of Fame inductee who many locals may remember is Bud Moore, a strong ally of Milner. According to his own memorial plaque, Moore “changed the face of the U.S. Forest Service, advocating for wilderness and as a district ranger in Idaho, famously turning back a bulldozer that came to build a road through what would become the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness. He became the chief of fire management for the Forest Service’s northern region, shaping the philosophy from one of fire suppression to recognizing fire’s ecological role in nature.”

Retired Bitterroot National Forest District Ranger Dave Campbell, who helped implement the agency’s new “let it burn” policy in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness, called Moore “the visionary behind the program.” He said Moore, Bob Munch, Bill Worf, and Doris Milner pushed hard for it and then Forest Supervisor Orville Daniels decided he’d give it a try.

The policy has now been implemented for over 40 years and has produced a treasure trove of information about the role of fire in a wild and natural environment.