The great sugar beet factory debacle

One of Hamilton’s iconic pieces of architecture, the large smokestack that looms like a giant watchtower over the north end of town, catches everyone’s eye as they enter or leave the city via Veterans Bridge. It’s an impressive sight, whether you know anything about its history or not. But when Ravalli County purchased the property that it sits on and headquartered the Ravalli County Search and Rescue in the small building at its base, it became an object of special interest to one of those search and rescuers, Joe Frechette, who has researched and compiled extensive material on the history of the stack and shared it with the Bitterroot Star on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of the stack.

What was meant to stand as a beacon of progress now stands as an icon to unrealized dreams. Like a couple other early and significant developments in the “Bitter Root” valley (as it was spelled at the time), the story of this old smokestack is the story of a failed effort at economic development. If not on par with the great Apple Boom, then pretty close behind it.

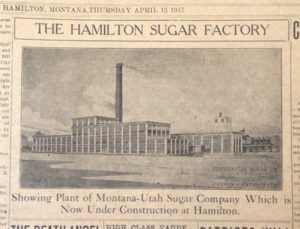

It was on April 12, 1917 that the Hamilton Sugar Factory made the front page of The Western News. Or more accurately, a picture of what it would be like once it was built. The Chamber of Commerce, it seems, had decided to show some “good faith” in the Montana-Utah Sugar Company, which had promised to build a factory here, by turning over the deeds to 80 acres of land north of town along the river in the little community of Riverside.

The news article accompanying the picture reads:

“You have made a binding contract with the company. No doubt you have been disturbed by rumors. The action of the chamber of commerce is evidence of its belief, and we ask that you likewise give no credence to these rumors.

“As you know, Ravalli County has had a bitter fight to secure this factory for the county. The same interests that have for months been trying to deprive the county of this advantage are still at work. In fact rumors predicting the Montana Sugar Company’s failure to build a factory, can generally be traced and said to follow a visit to the valley by an agent or agents of these interests.

“We ask you to join us in helping to support the Montana-Utah Sugar company. They have come here upon our request and upon our solemn pledges. We owe it to them to help them in their work.

“More than that, we owe it to ourselves. Every acre lost to the company is a loss to the valley. You will help yourself and the valley most by giving a loyal support to the Montana-Utah Sugar company.”

A big battle rampant with rumors over an economic development plan? Some things haven’t changed in the Bitterroot valley, it seems, no matter how you spell it.

But, despite the divisiveness, a few weeks later the newspaper states unequivocally that “a modern mill is now being erected.” It states that over 5,000 acres of land had been pledged by local farmers to grow beets.

“A fine profit is ensured,” states the article, “with a contract price of $7 per ton.” The article notes that the first train carload of beet seed had already passed through Minnesota and was being expedited. The company offered to help do the planting and had assembled a crew of 225 men to weed, thin and top the crops. A “battery” of beet seeders, pulverizers, and furrowers was already parked at the building site.

“Any person who doubts that the Hamilton factory will be built should visit the site near Riverside,” states the article. “There he will find the foundation laid, most of the concrete having been poured into the forms, and other evidences that will probably convince him, however much against his will.

“No such word as fail occurs in the lexicon of such men as George E. Saunders, O.C. Beebee and other men behind the Montana-Utah Sugar company.”

Some of the modern innovations being touted about the planned factory included the use of a conveyor belt and a completely automated cutter which eliminated the cutting job and was able to slice from 600 to 800 tons per day.

Northwest Construction company was given a subcontract to construct the smokestack 165 feet high and 150 feet above the floor of the factory, ten feet in diameter at the top and 14 feet at the bottom. It was to be constructed out of concrete and lined inside with fireclay brick.

“A few suggestions may be of value to those who are concerned especially since the beet game is a new one in the Bitter Root valley and many are skeptical as to the outcome of the venture. Serious attention should be given to the advice of those who have made beet growing a life study and practice,” company officials stated at the time. The suggestions had mostly to do with how to raise good beets. But growing beets was not really a problem, it was getting the factory built to process them.

Although things were divisive, the project seemed to be rolling along pretty well with crops looking good on about 3,000 acres and construction continuing at a good pace with materials and machinery pouring in when “ the blow fell,” as it was phrased in The Western News, and construction was temporarily halted at the site. According to The Western News, the Great Western Sugar Company, the behemoth in beet production in the region, which had a factory in Billings, had plans to build a factory in Missoula.

“Then it was determined that the Hamilton factory must be snuffed out and the beets from the Hamilton plant would be ground in Missoula. With its vast financial resources and ramifications everywhere representatives of the trust temporarily at least succeeded in hamstringing the Montana-Utah in connection with the flotation of a bond issue and now its agents are busy among the Bitter Root farmers seeking to divert the beet acreage to Missoula,” states The Western News.

Former Governor William Spry, who happened to be the President of the Montana-Utah Sugar Company, came to Hamilton to make a plea in support of the $500,000 bond needed to build the plant. He told the chamber of commerce that $400,000 in bonds had already been sold. To make the deal more palatable, “It was suggested that material assistance could be rendered at this time and a splendid moral effect created that would doubtless make certain the completion of the plant if Bitter Root people would subscribe for $50,000 worth of these bonds, with Utah people taking the remainder.”

But finally it was a motion by newspaper editor Miles Romney, seconded by Judge McCulloch, that drew unanimous approval for the appointment of a committee to solicit subscriptions to the bond issue to see the Hamilton and the Stevensville plants completed, and the fight was on.

Utah backers put up enough cash to keep the construction process going and work proceeded. The smokestack was about half complete. The foundation was almost finished. Half the structural steel was in place. Construction of beet sheds had begun. Excavation was underway for the pulp silo. And the machine shop was busy.

Field labor was hard to come by, however. The newspaper reports that “Russian, Japanese, Mexican and Filipino labor has been employed in the beet fields of the Bitter Root this season but the supply is wholly inadequate.” The company turned to using child labor. Company representatives made an appeal to the parents and the schools and were extremely appreciative of the community’s response.

“Through the patriotism and industry of about one hundred school children, a considerable saving will result to the beet growers of the Bitter Root valley,” it stated in The Western News. “In speaking of the help that the company had received from the children Assistant Manager Harmon said that the company deeply appreciated this effort and would be glad to use the service of double the number,” it stated in the newspaper. “The company was glad to know that money paid them was being kept in the valley and that if it were possible the company would like to have their entire wage payments kept here at home to build up the community.” The kids earned from 75 cents to $3 a day.

Boosted by the help from the community’s children the farmers continued to struggle on with their crops but the processing plant did not materialize. By August the Chamber of Commerce had to face the issue and “the question of the disposal of the beet crop of the Bitter Root valley was discussed and the directors decided that in the event that the Montana-Utah Sugar company had not shown its ability to care for the crop this season action be taken by the Chamber of Commerce to safe-guard the interests of the farmers….” It was suggested that the beets could be shipped to a factory in Utah or as an alternative fed to livestock. The claim was made that beets have greater value for stock feed than timothy or alfalfa.

When Montana-Utah Sugar company’s efforts failed, blame was laid on the doorstep of the Great Western Sugar Company which was trying to “snuff out” the Hamilton plant. Others placed the blame on the bond market at the time which was flooded with War Bonds. Grain prices were also high and there was a market for grain during the war.

For whichever reason or all of them, the smokestack was completed but the factory at Riverside was never built.

The plant in Missoula was built but Bitter Root farmers were a little slow in getting on board. For one thing, the distance from the fields to the railroad, located on the west side of the valley, was too far for the farmers to transport more than one wagon load of beets per day, which didn’t make the crop economical for the farmers to continue raising beets.

But things turned around when Otto E. Quast became instrumental in the re-introduction of the cultivation of sugar beets in the valley. By 1928 the railroad had been moved from the west side of the valley to the east side, which reduced the time spent by farmers to haul the beets to the railroad beet dumps and Quast got the agreement of the area farmers to commit a portion of their acreage to sugar beets. The beets were taken to Missoula by train to the Great Western Sugar Company refinery to be processed into sugar and molasses. The beet tops were used for cattle feed. Quite a few Bitterroot valley farmers prospered raising beets: the Hagen brothers, Jim Winters, Gib and Morris Strange, Ed O’Hare, Norris Nichols, Albert and Joy Wood, Otto Quast, and W.S. Bailey, to name a few.

The Missoula sugar refinery operated for decades before its doors were permanently closed in 1966.