National Institutes of Health scientists and their colleagues have found evidence of the infectious agent of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) in the eyes of deceased CJD patients. The finding suggests that the eye may be a source for early CJD diagnosis and raises questions about the safety of routine eye exams and corneal transplants. Sporadic CJD, a fatal neurodegenerative prion disease of humans, is untreatable and difficult to diagnose.

Prion diseases originate when normally harmless prion protein molecules become abnormal and gather in clusters and filaments in the body and brain. Scientists hope that early diagnosis of prion and related diseases—such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and dementia with Lewy bodies—could lead to effective treatments that slow or prevent these diseases. Scientists from NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) collaborated on the research with colleagues from the University of California at San Diego and UC-San Francisco.

Dr. Byron Caughey, a senior investigator in NIAID’s Laboratory of Persistent Viral Diseases at Rocky Mountain Laboratory in Hamilton, said that clinicians in California were able to collect eyes from eleven deceased CJD patients who had donated them to science, dissect them and send the samples to RML for testing.

Caughey and his associates used their highly sensitive test, called real-time quaking-induced conversion (RT-QuIC), that detects prion seeding activity in a sample as evidence of infection.

According to Caughey, it was already known that CJD patients do carry prions in their eyes and that they can be transmitted in surgical procedures to other people. He said two “definite” cases have been confirmed in cornea transplants in which CJD prions were transferred to the cornea recipient and a few more cases of “suspected” transmission. Prion infectivity has also been reported from human cornea inoculated into mice.

This is important for a number of reasons. Corneal transplantation is an increasingly common surgery, with 185,576 corneal transplantations performed in 116 countries in 2012, more than ever reported previously. The United States leads in corneal procurement and transplantation per capita, with approximately 64,000 corneal transplants per year. It is estimated that 40% of sporadic CJD patients develop eye problems that could lead to an eye exam, meaning the potential exists for the contamination of eye exam equipment designed for repeat use.

Caughey said “It is known then that some CJD patients have it in their eyes. Our study was designed to answer two further questions. What portion of CJD patients have it in their eyes? And how much is located in each component of the eye?”

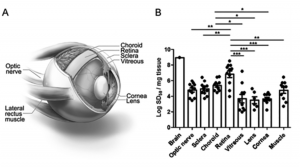

“The upshot is” he said, “we found evidence for prions in eyes of all eleven CJD patients and in multiple parts of each eye.” Some parts have more than others. Caughey said the retina contained the highest concentration next to the brain, but other parts had significant amounts of prion seeding activity. Besides finding prion seeds in all the corneas, they were also present in the optic nerve, extraocular muscle, choroid, lens, vitreous, and sclera and elsewhere.

“Collectively, these results reveal that CJD patients accumulate prion seeds throughout the eye, indicating the potential diagnostic utility as well as a possible biohazard,” states the published report.

“It certainly supports concerns about the possibility of transmission of CJD especially in corneal transplants,” said Caughey, “but also contamination of instruments used in ophthamological procedures in the clinic.”

“But that’s not to say the sky is falling,” Caughey was quick to add. He said there was no indication of a huge problem of this kind of thing happening. “But it certainly suggests that vigilance be applied to the potential risks of contamination.”

He said it may be wise to minimize the re-use of medical instruments, especially ones that cut into the eye and to use disposable instruments when possible. He said that harsher-than-usual treatments must be used to disinfect prions relative to other types of pathogens such as bacteria or viruses.

Aside from invasive medical procedures, he said, there is no epidemiological evidence to suggest that CJD can be transmitted through any sort of casual contact.

One thing we still don’t know is how early in live patients the prion activity shows up in the eye, but Caughey says that experiments in mice have shown that it can show up quite a bit earlier than the other clinical signs of the disease. This raises the possibility that eye fluids or any other easily accessible component of the eye might be useful as a diagnostic specimen in order to better diagnose CJD in people.

Currently the normal diagnosis requires testing spinal fluid with a lumbar puncture or a swabbing from the nasal cavity, “But if you could get an easily accessible sample from some area of the eye, maybe that would be helpful and preferable to a spinal tap or nasal swab,” said Caughey. He said they have not yet done any tests on tears but that those tests were on the horizon as they continue to look for answers in their research.

“We are also keen to look at the eyes of people with other protein disorder diseases,” said Caughey. Some diseases, like Alzheimers, Parkinsons, dementia with Lewy bodies and other neuro-degenerative diseases also involve the accumulation of certain misfolded proteins that can propagate within people much like prions. He said they would like to develop a real-time quaking-induced conversion test for these types of diseases and see if the problematic proteins related to those diseases also accumulate in the eyes.