by Michael Howell

Thanks to the work of scientists at Rocky Mountain Lab in Hamilton, Montana hunters can feel a lot more at ease eating their venison this coming season. Ever since Chronic Wasting Disease – a fatal, infectious neurodegenerative disease that is highly transmissible among cervids such as deer, elk and moose – entered Montana, there has been a cloud of concern over the question of whether the disease could be transmitted to humans by eating the meat of an infected animal. A new study released last week, using a human cerebral organoid model, suggests there is a substantial species barrier preventing that kind of transmission. The findings, from National Institutes of Health scientists and published in ”Emerging Infectious Diseases,” are consistent with decades of similar research in animal models at the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

It was a scary prospect. Prion diseases are degenerative diseases found in some mammals. These diseases primarily involve deterioration of the brain but also can affect the eyes and other organs. Disease and death occur when abnormal proteins fold, clump together, recruit other prion proteins to do the same, and eventually destroy the central nervous system. Currently, there are no preventive or therapeutic treatments for prion diseases.

There was reason to be concerned as well, because during the mid-1980s and mid-1990s a different prion disease – bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), or mad cow disease – emerged in cattle in the United Kingdom (U.K.) and cases also were detected in cattle in other countries, including the United States. Over the next decade, 178 people in the U.K. who were thought to have eaten BSE-infected beef developed a new form of a human prion disease, variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, and died. Researchers later determined that the disease had spread among cattle through feed tainted with infectious prion protein. The disease transmission path from feed to cattle to people terrified U.K. residents and put the world on alert for other prion diseases transmitted from animals to people, including CWD. CWD is the most transmissible of the prion disease family, showing highly efficient transmission between cervids.

Historically, scientists have used mice, hamsters, squirrel monkeys and cynomolgus macaques to mimic prion diseases in people, sometimes monitoring animals for signs of CWD for more than a decade. In 2019, NIAID scientists at Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Hamilton developed a human cerebral organoid model of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease to evaluate potential treatments and to study specific human prion diseases.

Human cerebral organoids are small spheres of human brain cells ranging in size from a poppy seed to a pea. Scientists grow organoids in dishes from human skin cells. The organization, structure, and electrical signaling of cerebral organoids are similar to brain tissue. They are currently the closest available laboratory model to the human brain. Because organoids can survive in a controlled environment for months, scientists use them to study nervous system diseases over time. Cerebral organoids have been used as models to study other diseases, such as Zika virus infection, Alzheimer’s disease, and Down syndrome.

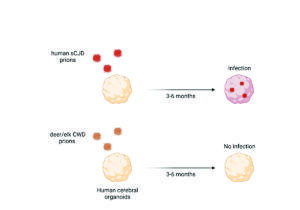

In the new CWD study, the bulk of which was done in 2022 and 2023, the research team validated the study model by successfully infecting human cerebral organoids with human CJD prions (positive control). Then, using the same laboratory conditions, they directly exposed healthy human cerebral organoids for seven days with high concentrations of CWD prions from white-tailed deer, mule deer, elk, and normal brain matter (negative control). The researchers then observed the organoids for up to six months, and none became infected with CWD.

“We are optimistic,” said lead author of the study Cathryn Haigh, chief of the Prion Cell Biology Unit in NIAID’s Laboratory of Neurological Infections and Immunity. “Ever since we developed the human organoid model we thought that it was a good idea to see if CWD infectious proteins could infect the human organoids. I can’t imagine a situation in which a human brain would ever get an exposure [to such high concentrations] like that. So, the fact that the organoids didn’t get an infection is a very promising sign of a very strong species barrier.” Making it extremely unlikely to contract a prion disease because of inadvertently eating CWD-infected cervid meat.

The latest study does not, however, put a nail in the coffin to the question as to whether CWD might in some rare cases be transmissible to humans who have some special susceptibility or transform itself into a version that is more easily transmittable to humans.

“The study has a number of limitations,” said Haigh. “One of them is rare genotypes in humans that might be susceptible.” She said they were currently looking into one of those rare genotypes.

“We also think that, theoretically, if you were to eat CWD it would infect your guts before it infected your brain,” said Haigh. “So, we want to have a look at human organoid gut tissues to see if maybe that tissue was susceptible. If it is not, then that would make it extremely unlikely that the disease would be able to jump.”

“There is also the possibility that a new strain may emerge,” she said. “We hope not. But if they do, we can look at those with this model as well.”