by Michael Howell

Like the art of fly fishing and fly tying itself, Les Korcala came over to America from Europe, landing on the East Coast before eventually making his way out to the place of his dreams and settling along the banks of the Bitterroot River with his wife Cheryl.

Korcala was born in Krakow, Poland, under communist rule, in 1960. He recalls being frightened when he first arrived in the United States in 1981. He was standing next to his luggage in the airport when a man grabbed his suitcase from right in front of him. He thought he was being robbed. He quickly realized it was just a baggage man trying to help. But then he was taken over and someone grabbed his hands, pressed his fingers into an ink pad and took his fingerprints. The experience was unsettling.

That first impression didn’t last for long, however. One trip to the grocery store made a deeper, more lasting impression.

“I’d never seen so much chocolate and oranges,” said Korcala. “We never had things like that in grocery stores under the communist government in Poland.” Korcala said he realized then that he had arrived in the land of freedom and opportunity.

It was while living in Connecticut that he was first introduced to the art of fly fishing. He said his passion for fly fishing really started with old style wet flies that he fished back then. Fly fishing as we know it today, he said, originally started back in England, where only wet flies were used. Dry fly fishing hadn’t been invented yet. He said that the use of wet flies in the U.S. began in the area around New York, New Hampshire and Vermont in the 1800’s. So, Connecticut was a great spot to learn about wet flies and the early days. What he calls the “Golden Age of fly fishing.”

Those flies were designed to fish for brook trout and some of the salmon around that area in the late 1800s. Although the first brown trout eggs from Germany had arrived, the flies being tied were specifically for brook trout.

Korcala’s passion for old style wet flies remains strong. If anything, it has only grown stronger with the move to Montana, even given the addition of dry flies to the mix. He also has a great fondness for using natural materials in his fly-tying work. But he has also picked up the modern styles that incorporate artificially manufactured materials. He’s always trying new things, while holding immense respect for the old.

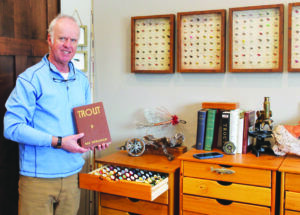

He has the same sustained enthusiasm for the history of fly fishing and fly tying as he does for tying the flies and actually catching the fish, it seems. He is most proud of his signed copy of a first edition of Ray Bergman’s book “Trout.” The book was first published in 1938 with nine color plates of flies painted by Dr. Edgar Burke. The book was popular right out of the gate and that first edition was reprinted 13 times. Then in 1952 the book was reset and printed from new plates. This second edition not only contained additional color plates, it also contained new chapters on fishing for trout with spinners. This edition was reprinted for the fifth time in 1965.

Korcala said that after retiring and moving to Montana, he had more time on his hands and began collecting bugs and learning all he could about hatches and began tying new patterns. Then about four years ago he came across the late Don Bastian’s website and all the beautiful wet flies he had tied based on Bergman’s plates.

“Learning about the wet flies, their origins, names, and the stories behind each pattern, I was quickly inspired and started to tie a few patterns from his website,” said Korcala.

He found further inspiration in the work of John McCoy, who also tied winged wet patterns, and studied his work thoroughly.

“Then last winter I decided to tie the entire Ray Bergman collection of nine plates and 440 wet flies included in his book,” said Korcala. He completed that endeavor last spring.

“These flies are complex and take a lot of skills to master,” said Korcala. “Good materials are critical. I searched many shops and reached out to friends to find the right materials, textures and colors. Materials have gotten more sophisticated over the years and Solarez Bone Dry Black is one such example. It made all the difference in the final finish of the heads on the flies. Quality of the feathers is also critical. My wife and I have experimented with different threads, hooks, and found a few of our favorites. Tying, then trying the flies in our home waters.”

Another hurdle in tying Bergman’s fly patterns is that some of the materials used are not available at all today. Some of the feathers used, for instance, were from birds that are now illegal to use or they are extinct, like the famous Red Ibis. Mallard feathers can be used as a replacement for some colors by being dyed. Only portions of the quill can be used, but four or five pairs of wings can usually be made out of one quill.

Thread is also important. You need all colors and all textures. Korcala’s hobby room has large desks with drawers full of spools of thread of many textures including silk, floss and even metal wire, and feathers, feathers and more feathers. Then there’s the animal fur and hair, including deer and moose, etc. He gets some of his hackles from Charlie Cohen in New York.

According to Korcala, a lot of people have tried to make all 440 flies in the Bergman plates, but many fail to finish. He knows one fellow who took five years to complete the project. He knows another who quit but came back 10 years later to finish the job when he had more time to put into it.

“You have to be really determined to do this because you have to keep going,” said Korcala.

So, he set a goal last winter to tie three to six flies a day, tying four or five times a week with only one day off. It took him about six months.

He now has a few tips to share with anyone contemplating such an undertaking, like, if you want all the frames to match, for instance, you’d better buy them all at once. It takes nine frames to hold the Bergman selection. He also uses all the same size hooks, a #8. He uses specially selected paper for backing that looks like parchment and selected an elegant style font. Everything in the frame must be balanced and evenly spaced. He does this by eye without measuring.

When he’s not tying flies, or reading about fly fishing, he really is out fishing. His wife Cheryl, who also ties and has her own work desk in their hobby room, joins him on many fishing escapades. He and his wife fish catch-and-release; “We put the fish back,” he said.

Although they can fish the Bitterroot River by walking out their back door, for most of the summer they fish in the many streams that lace the watershed. Korcala said that he measures the temperature in the river regularly at varying depths and can confirm that the water is too warm during the deep summer with irrigation underway.

“We go and fish the streams, until the water cools off in the fall,” he said.

fishing gear. He donates such items for auction to local non-profits like Trout Unlimited to

raise funds for the organizations.

Korcala’s passion for fishing and fly tying spills over into other aspects of his life where he turns the art of fly tying into fly-tying art. Literally. Sculpted trout swim across the lintel of their fireplace. An artificial fly the size of a golden eagle graces their living room wall. Sculpted trout also appear on the back of a bench designed with a compartment to hold fishing gear and provide a place to sit and put your waders on.

Les and Cheryl are very active in the community, donating time to watershed restoration projects and children’s fly tying classes as well as donating various art pieces, like the fly fishing bench, to the local Trout Unlimited auctions.