A team of scientists from the University of Montana has been measuring water flows in three streams that emerge from the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness on the west side of the Bitterroot Valley for a couple of years now. The monitoring, being done on Lost Horse Creek, Mill Creek and Bass Creek, is providing supplemental information related to a greater experiment aiming to calculate the total load of water being stored and released annually by the entire Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness watershed.

Leading the local water gaging effort in the Bitterroot is Dr. Payton Gardner, Associate Professor of Hydrogeology at the University of Montana and Associate Editor of the Journal of Hydrology at UM, who obtained the grant funding to install continuous recording flow measurement devices to help measure the discharges and the timing of discharges along one section of the greater study area.

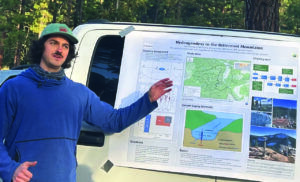

Brett Oliver, a graduate student in geoscience at the University of Montana participating in the project, gave local citizen-science volunteers from the Bitterroot River Health Check a view of the big picture before giving them a lesson in water gaging at the Lost Horse Creek site last weekend.

The big picture is big indeed and covers a major portion of the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness. It involves surrounding the entire watershed with a ring of highly sensitive GPS positioning antennas anchored into bedrock which record the rise and fall of the earth’s surface. The scientists will then correlate this data with data about the amount of precipitation and snowpack/water equivalent data in the area. What they know from data already collected in the region is that the amount of depression in the earth’s surface in a given area appears to an inverse curve compared to the amount of snowpack/water equivalent in the area.

Oliver said that in the arid West we are quite reliant on the mountain systems for our water supply. Mountains are higher and consequently get more precipitation and they get colder than the lowlands and the valleys and are thus a primary form of water storage for the lower elevations.

“So, it’s really important that we understand hydrologically what is happening up in the mountains in order to understand our water resources and to prepare for times of plenty and times

of scarcity, through droughts, floods or whatever,” said Oliver.

One of the challenges in understanding hydrology in the mountains is that they are really diverse areas in terms of climate and range. They are large, expansive and remote, often difficult to access and as a result there is not a lot of data.

“The idea behind this experiment,” said Oliver, “is to develop a better method to estimate water storage in mountainous areas because they are critical to the Western U.S.”

He said his team was working with a new technology and a new kind of science called Hydrogeodesy, that is, actually observing the curvature of the earth in order to infer something about processes that are changing the earth’s shape.

It is new developments in satellite technology yielding extremely accurate and precise measurements at a very minute scale that make the research possible. In a network of stations around the watershed, GPS stations are installed that communicate their location to a satellite. As ice and water build up in the watershed, the earth becomes depressed like a mattress with a bowling ball sitting in the middle of it. The antennas secured into the bedrock begin to sink and tilt toward the load. When the load is removed the antennas return to their initial position. The movement is constant, according to Oliver, so the earth’s crust is always moving lightly up and down throughout the year, always fluctuating. The calculations are not simple and involve removing other factors, such as atmospheric pressure and the effect of tides.

Kent Myers said he was happy to get the chance to learn how to take water measurements and learn about an aspect of water quality monitoring that he hadn’t been engaged in but some of his cohorts in the Bitterroot River Health Check program do regularly.

Myers is team leader of the north Bitterroot River Mainstem project where volunteers collect water samples and have them laboratory tested for nitrogen, phosphorous and other potential pollutants. They also collect data on key parameters such as temperature, conductivity, pH, percent of dissolved oxygen, turbidity, etc. Flow measurements for the river are taken from the USGS gages placed along the river to estimate loads.

Volunteers from the Bitterroot River Health Check program have also been lab testing laboratory samples and collecting the other parameters on six tributaries coming out of the Sapphire Mountains on the east side of the valley for five years but have only been gaging associated flow measurements for the last two years.

“Our aim since 2018 has been to establish a permanent network of water quality and quantity measuring stations on every major tributary to the mainstem of the Bitterroot River,” said Bitterroot River Protection Association (BRPA) spokesperson Greg Pape. BRPA has played a leadership role in the Bitterroot River Health Check program since it was formed.

“We were excited to learn about this water gaging experiment on these tributaries on the West side,” said Pape. “We were already eyeing the Bitterroot Front as our next area of expansion as we reach beyond the mainstem of the river and the Sapphire Front. Having recently signed an MOU with the Bitterroot National Forest to do just that we were pleasantly surprised to see the University of Montana showing up with a similar interest and have been cooperating with them since they arrived.”

Pape said that UM professor Payton Gardner told his group that funding for the university’s current project was only scheduled to last for three years and that after that time control and operation of the sites may be left behind to serve as permanent sites in the Bitterroot River Health Check’s planned network for perpetual monitoring.

“Dr. Gardner worked closely with us in establishing these sites to ensure that they would also serve as good sites for our plans on the whole Bitterroot Front,” said Pape. “It is worth noting,” he said, “that the site on Lost Horse is already supplying data that is of interest to other organizations.” In this case it is the Clark Fork Coalition’s recent project to install a fish screen on Lost Horse Creek at the BRID canal diversion that will benefit from the data.

“We believe the data from all our sites will prove useful for a great number of individual, isolated and unique water related projects across the whole watershed as time goes by,” said Pape.