By Michael Howell

Most Bitterrooters are familiar with the Rocky Mountain wood tick (Rickettsia rickettsia) that proliferates here during the spring and summer months, the ones known to occasionally transmit such diseases as Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and Colorado Tick Fever to humans. But another type of tick, Ornithodoros hermsi, not so well known and not so easily noticed, even when they are doing their bloody business, has now been conclusively identified as inhabiting the Bitterroot Valley following an investigation into the case of a Corvallis area resident who contracted Relapsing Fever in 2013.

Unlike Rocky Mountain Fever, which can be treated with antibiotics, Colorado Tick Fever cannot. But the disease will run its course. After peaking and subsiding, and then peaking for a second time, it will subside for good.

Relapsing Fever, on the other hand, will peak and subside, peak and subside, again and again until treated. If the series of intense fevers and other symptoms continue without treatment long enough it could result in mortality. However, Relapsing Fever can be treated with antibiotics, the key being proper diagnosis.

A study of the Corvallis infection was recently posted online January 8 in the CDC journal Emerging Infectious Diseases under the title: “Tickborne Relapsing Fever, Bitterroot Valley, Montana, USA,” by Joshua Christensen, an infectious disease specialist at St. Patrick Hospital and the University of Montana, along with Robert J. Fischer, Brandi N. McCoy, Sandra J. Raffel, and Tom G. Schwan from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Rocky Mountain Laboratory. It will be printed in the February edition Volume 21, Number 2, February 2015.

The 55 year old Corvallis man, after a week of fevers in July 2013, sought care at the emergency department of a Missoula hospital showing signs of fever, chills, night sweats, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and malaise. He was dismissed from the hospital after a presumptive diagnosis of an acute viral infection. But he returned two days later with more serious symptoms.

A blood smear was taken and a certain type of bacteria (spirochetes) were observed under the microscope, swimming amongst the blood cells. Their identity was confirmed, in a sample sent to the Centers for Disease Control, as Borrelia hermsii, the bacteria that causes Relapsing Fever.

The Missoula doctors involved were not totally unfamiliar with the disease. The first documented outbreak in Western Montana had already occurred on Wild Horse Island during the summer of 2002. Five persons, all of whom resided elsewhere, became infected while sleeping in a tick-infested cabin during a family reunion. In 2004, three more persons became infected with B. hermsii while sleeping in another recreational cabin on the island, a short distance east of where the first outbreak occurred. Isolates of B. hermsii were obtained from the two patients infected in 2002 and the three patients infected in 2004.

Recognizing the Corvallis case as a tickborne disease, the question arose as to where it had been contracted. There was no record of this tick being found in the Bitterroot Valley and the man had recently traveled extensively, including trips to Antarctica, New Zealand, Spain, Italy, and eastern Washington state.

The doctors quickly turned to Rocky Mountain Laboratory for help. After all, that’s where seminal scientific study of tickborne diseases had begun more than a century ago with the discovery in 1906 that an illness locally called black measles, which affected persons in the Bitterroot Valley, resulted from the bite of a bacteria-infected Rocky Mountain wood tick. What soon followed was the establishment of a multidisciplinary public health program to control this newly identified disease, now called Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, and a search was conducted for other diseases in nature that resulted from the bite of pathogen-infected ticks. These programs were based at the newly funded state laboratory in Hamilton in the Bitterroot Valley. The facility was soon incorporated into the US Public Health Service and is now our own Rocky Mountain Laboratories (RML) of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

One of the many diseases studied at the RML since the early 1930s has been tickborne relapsing fever in North America. It has been found in scattered foci in the western United States and southern British Columbia, Canada, and finally in western Montana on Wild Horse Island, but never identified in the Bitterroot Valley… until now.

Tom Schwan, a lead investigator at the Laboratory of Zoonotic Pathogens at RML, said, “Those doctors deserve credit for being alert, being knowledgeable, recognizing what they were dealing with, and getting the best help available.”

The bacteria, or spirochetes, were confirmed in the blood samples the lab received. A sample was inoculated into a mouse to amplify and isolate some spirochetes for DNA testing and the samples were definitively identified.

“Given the patient’s date of onset of illness, travel history, and reported incubation periods for the infection, an average seven days, with a range of four to18 days, we concluded that he was possibly infected on his own property,” said Schwan. So Schwan and a team from the lab including Ron Fischer, Brandi McCoy and Sandra Raffel, went to the property east of Corvallis where the man remembered moving part of a woodpile and noted rodent feces among the cut logs.

Not only did the team discover the ticks in the woodpile, they were able to lure and trap others with CO2 traps baited with dry ice. The nocturnal feeders will follow a CO2 trail to a host for feeding.

“We also collected debris from the woodpile and processed the material by using Berlese funnels in an attempt to extract live ticks,” said Schwan. They succeeded in finding the spirochetes in four of nine ticks. They were able to identify spirochetes in a chipmunk that was trapped and tested and they were able to match those with the ones in the tick as well as the ones in the man’s blood.

Schwan said that, by coincidence, at the time of the patient’s illness, the lab had already begun a preliminary field study in the Bitterroot National Forest to search for evidence that B. hermsii might be present. At two sites, one at Lake Como and one at Hughes Creek, eight species of rodents that included 178 animals were captured. None of the animals exhibited microscopically detectable spirochetes in their blood when captured. However, immunoblot analysis of serum samples demonstrated that nine animals representing four species were seropositive, which indicated they had been previously infected with spirochetes.

These animals included one red-tailed chipmunk at Lake Como and five chipmunks of the same species at Hughes Creek. Additional seropositive animals at Hughes Creek included a northern flying squirrel, one golden-mantled ground squirrel, and one western jumping mouse. Subsequently O. hermsii ticks were also trapped at Hughes Creek and confirmed as carrying spirochetes.

According to the article about to be published, the results of the study showed “that the slopes of the Bitterroot Valley and surrounding areas represent a newly identified area to which B. hermsii spirochetes are endemic, which has the potential for being a source of human infections in this region of Montana.”

“Among wild rodents we sampled, seven (70%) of 10 animals that were seropositive were chipmunks, and one yellow-pine chipmunk was infected with B. hermsii when captured. In other areas of the western United States, these animals play a major role as hosts for O. hermsi ticks and B. hermsii. Therefore, our observations extend considerably the geographic range for chipmunks involved in a natural enzootic focus of relapsing fever,” states the report.

“The patient with relapsing fever described in this report represents another example of an atypical exposure by becoming infected during a daytime activity. Although O. hermsi ticks are nocturnal and typically feed at night, persons who disturb materials infested with these ticks during the day might be bitten and become infected. We investigated a similar daytime exposure for a relapsing fever patient who was bitten by ticks while moving rodent-contaminated debris at Mount Wilson Observatory in Los Angeles County, California, USA. However, most persons in whom relapsing fever caused by B. hermsii develops are exposed at night in recreational cabins that are not the patient’s primary residence,” it states in the report.

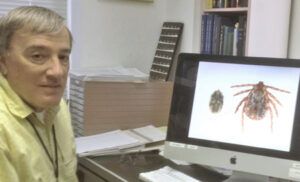

According to Schwan, unlike the Rocky Mountain wood tick which embeds itself and latches on to its host for long periods, this little tick bites and runs.

“So people do not even realize they have been bitten when they wake up in the morning,” said Schwan.

The report concludes, “Residents and visitors to the Bitterroot Valley need to be alerted that there is the potential for becoming infected locally with the relapsing fever spirochete B. hermsii. Tickborne relapsing fever should be considered when patients seek treatment for a history of recurrent, acute febrile episodes. Confirmation of the infection is made most often by visualizing spirochetes in a stained, thin blood smear made during a febrile episode and examined by a trained medical technologist, as was performed for the patient in our study. In addition, this area of Montana has long been a popular tourist destination for visitors from other regions of the United States, where the opportunity exists to enjoy many outdoor recreational activities. Health care providers in other parts of the country need to be aware that persons spending time outdoors in and around the Bitterroot Valley of Montana may be exposed to spirochetes causing relapsing fever in this newly identified disease-endemic area far from their place of residence.”