by Michael Howell

Recent news that President Trump had issued an Executive Order that would require four federal agencies to prepare a list of high priority mining projects to be accelerated using a “fast-tracked permitting process” and “streamlining” of environmental review raised an immediate alarm among local conservation organizations about U.S. Critical Mineral’s proposed Sheep Creek Mine in the headwaters of the Bitterroot being placed on the list. As it turns out, although no one at the Bitterroot National Forest could confirm this on Monday, the Federal Permitting Improvement Steering Council’s initial list does not yet include the Sheep Creek Mine. In fact, the only mine in Montana that made the list was the Libby Exploration Project in the Cabinet Mountains. But as the Council notes in its listing, “This is just the beginning—many more projects are expected to be added to the list on a rolling basis over the next few weeks.”

On January 20, 2025, his first day in office, President Trump signed a “National Energy Emergency” proclamation (Executive Order 14156), signaling the Administration’s intent to use broad measures, such as fast-tracked permitting and invocation of authorities under the Defense Production Act (DPA), to boost U.S. energy and mining independence, including the construction of energy infrastructure and the production of critical minerals within the United States.

In March the administration began rescinding prior climate-focused Executive Orders that it viewed as impediments to energy production and then on March 20, the President signed an EO entitled “Immediate Measures to Increase American Mineral Production” which includes aggressive timelines in which federal agencies are to take significant measures to fast-track permitting, leasing, and financing of domestic mining projects. The EO also includes provisions designed to re-allocate existing federal funds and incentives to increase private sector investment in the mining industry.

The order states, in part, “Within 30 days, four agencies – Interior, Defense, Agriculture (which manages National Forests), and Energy – must identify specific sites on the lands they manage that could be leased or opened up for private commercial mining development quickly, with a focus on those sites that could be ‘fully permitted and operational as soon as possible’ and that would have the biggest impact on U.S. supply chain security.”

The EO also contemplates certain longer-term regulatory modifications giving the National Energy Dominance Council (NEDC) chair and White House staff 30 days to recommend updates to the Mining Law of 1872 related to how waste rock and mine tailings are handled.

Although the EO does require that all actions be “consistent with applicable law” – which suggests that existing statutory and regulatory requirements (like the National Environmental Policy Act or the Endangered Species Act) will inform the scope of any new mineral extraction efforts that are undertaken pursuant to this order – the President’s previous declaration of an energy emergency and moves within the EO to accelerate permitting approvals are likely to increase the speed with which mining interests can expect federal action. The Administration is clearly willing to consider streamlining environmental reviews. For example, projects put on the FAST-41 Permitting Dashboard benefit from coordinated, and potentially shorter, NEPA reviews. And by waiving certain DPA requirements, the EO potentially signals that certain projects may be eligible for modified regulatory requirements.

A client alert issued by the law firm King & Spalding states, “It’s worth noting that many of the statutory tools being employed in the EO have rarely been used at this scale to promote mining and mineral processing… With the administration’s new Executive Order, the critical minerals supply chain is being treated explicitly as a national defense issue. The primary takeaway is that projects and investments that were previously considered marginal or to have a challenging permitting path might now become viable with federal help.

“At the same time, businesses will need to navigate the environmental and regulatory tensions that remain – not all red tape can be cut with an Executive Order, and legal challenges to federal decisions are certain to crop up. And there is the question whether, given reductions in employee headcount the Administration has imposed at most Executive Branch agencies, the federal agencies charged with implementing the March 20 Executive Order will be equal to the task. The coming months will reveal how effectively these ambitious directives can be turned into shovels in the ground and new supply chains that truly reduce dependence on foreign minerals.”

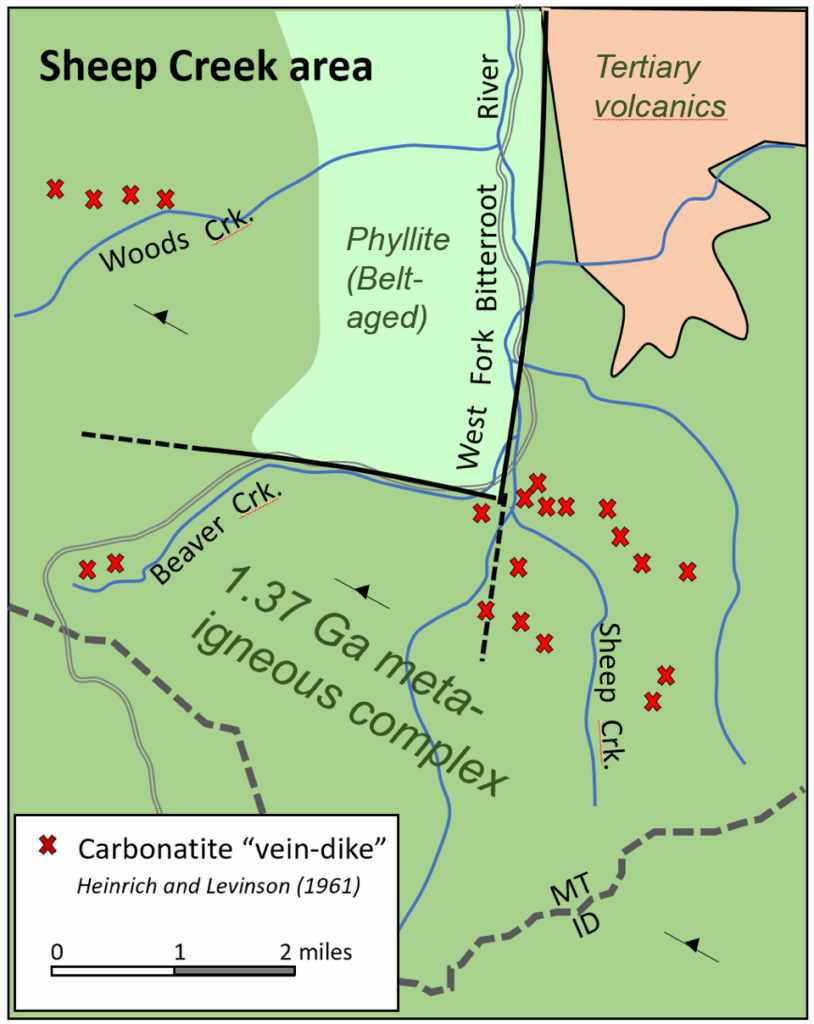

All of this has sparked concerns among local conservation organizations about the potential development of the Sheep Creek Mine in the headwaters of the Bitterroot River up the West Fork.

Bitterroot Water Partnership, for instance, issued “An Unprecedented Alert” expressing its concern that the order could potentially reduce environmental reviews and stating that a mine in the headwaters of the Bitterroot would pose a serious threat to our waters and our ways of life in the Bitterroot, and accelerating the review process would only amplify that risk. “We do not want the potential Sheep Creek mine on that priority list. We cannot afford a promisingly disastrous mine in the Headwaters of the Bitterroot,” states the alert.

The organization strongly advocates for other available options such as extracting rare earth elements from existing mine waste in Butte.

“This approach not only meets national needs, but helps clean up past pollution, offering a better solution for people, health, nature, and economies.”

Bitterroot Trout Unlimited has echoed the BWP’s concerns, stating in a recent newsletter that “our main concern is the mine’s location in the Bitterroot headwaters. The risks to our water, agriculture, and fisheries are too high. If developed, this mine would wreak unimaginable damage on the landscape and likely degrade water quality and quantity along not only the West Fork, but the entire river.”

Bitterroot Clean Water Alliance has also come out strongly against putting the U.S. Critical Materials’ Sheep Creek Mine on the federal priority list, stating that the mining claims are in an unsuitable location for a large mining operation, because the risks to “our drinking water, agriculture, and the renowned Bitterroot fishery are unacceptable.”

“The Department of Defense is already involved in a project in Butte, extracting these minerals from existing mine waste. This is a more sensible approach, cleaning up existing pollution while meeting national needs. Prioritizing the Sheep Creek mine would disadvantage a Montana-based solution that is already underway,” said Philip Ramsey, spokesperson for the Alliance. “The Sheep Creek project is at a very early stage. There is no plan of operations, and exploratory drilling hasn’t begun. This project cannot meet any immediate national need for critical minerals. Rushing it through the permitting process makes no sense.”

Andy Roubik, President of the Bitterroot River Protection Association, said that his group has been concerned about the impacts of the proposed mine since it was first proposed and had already instigated a water quality monitoring project in the area to gather information on the current status of two streams running through the area, Sheep Creek and Johnson Creek, as well as in the West Fork of the Bitterroot River above and below the mining claims.

“Initial results show that the streams and the river are in good condition,” said Roubik. He said initial testing for metals found nothing detectable in the water and only background levels in sediment.

“This area is home to some threatened macro-invertebrate species and to bull trout,” said Roubik. “We need to do everything we can to preserve the fisheries and the clean water that we currently have. The recreational, agricultural and real estate economies of the Bitterroot valley could all be seriously undermined by the kind of ecological devastation that historically accompanies these mining operations.”

When the list was made available, only one mine in Montana was on it. That mine is in the Cabinet Mountains near Troy.

West Fork District Ranger Dan Pliley said when contacted Monday morning that he was not able to comment on anything concerning the mining proposal or any priority list and was told to refer all those questions to Public Affairs Officer Tod McKay. Phone calls to McKay and to the Supervisor’s Office and to the regional office in Missoula were all answered by messaging machines and no answer was received by press time. The Bitterroot National Forest website was also dysfunctional, with a message saying that it was undergoing repairs and would be made available as soon as possible. It too was not online by press time.

Tracy says

LMMFAO